The Difference Between Virus, Malware, Spyware, and Ransomware

The vocabulary of cyber threats has expanded dramatically over the past two decades, yet terms like virus, malware, spyware, and ransomware are still frequently misunderstood—even among experienced users. As digital infrastructure becomes more complex and attackers adopt increasingly sophisticated techniques, distinguishing between these threat categories is essential for identifying risks, understanding attack behaviors, and deploying the correct defenses. This in-depth analysis breaks down how these threats differ, how they operate, and why their evolution reflects deeper trends in global cybersecurity. References from authoritative institutions such as NIST (nist.gov), CISA (cisa.gov), and leading universities (mit.edu, stanford.edu) provide a grounded, research-driven perspective.

Although the terms are often used interchangeably, malware is the umbrella category. Malware—short for malicious software—refers to any program intentionally designed to damage, disrupt, infiltrate, or manipulate computer systems. According to the National Institute of Standards and Technology at nist.gov, malware includes viruses, worms, trojans, spyware, ransomware, rootkits, and more. Understanding malware’s broader definition is crucial because attackers frequently blend multiple malware types to increase impact. Modern attacks often combine trojan loaders, spyware modules, and ransomware payloads in a single chain, demonstrating how intertwined these threat vectors have become.

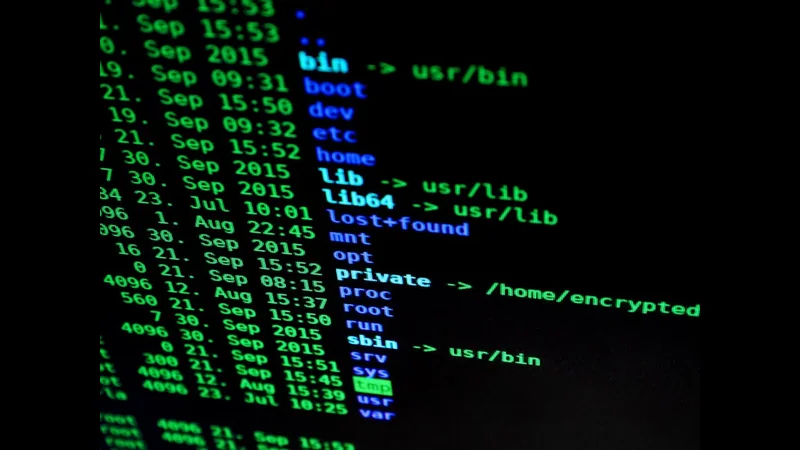

A computer virus is one of the earliest and most iconic forms of malware. It operates by attaching itself to legitimate files or programs and replicating when those files are executed. Viruses typically spread from one system to another through user actions such as opening infected documents, running compromised software, or sharing removable media. Early viruses were often disruptive pranks, but modern variants can wipe data, corrupt operating systems, or open backdoors for remote attackers. Research conducted at MIT (mit.edu) highlights that the defining characteristic of a virus is its dependence on host programs and user interaction for propagation. Unlike worms, viruses cannot spread automatically.

In contrast, a worm is a self-replicating program that spreads autonomously across networks. While not explicitly listed in the headline terms, worms are important for distinction because many users mistakenly categorize them as viruses. Worms exploit vulnerabilities in network protocols, unpatched software, or misconfigured services to spread without any user engagement. Historical worm outbreaks documented by CISA (cisa.gov) demonstrate how a single worm can infect millions of systems within hours. The capability to propagate automatically makes worms particularly dangerous in enterprise environments, where lateral movement can escalate quickly.

A trojan, or trojan horse, represents another major class within malware. Trojans disguise themselves as legitimate software or files to trick users into installing them. Once inside the system, trojans do not self-replicate but instead create pathways for other threats. Attackers frequently use trojans to deploy spyware, keyloggers, or ransomware payloads. Research from Stanford University (stanford.edu) shows that trojans serve as the backbone of many modern attack campaigns, functioning as modular entry points into compromised networks.

Spyware is a specialized category of malware designed to secretly monitor user behavior and collect sensitive information. It operates covertly, capturing keystrokes, browsing activity, system data, login credentials, and financial information. Some spyware variants activate device microphones or cameras, raising significant privacy concerns. Unlike viruses, spyware focuses on surveillance rather than disruption. The Federal Trade Commission (ftc.gov) warns that spyware often bundles itself with free software or browser extensions, using deceptive installation flows that appear legitimate. Spyware’s stealthy nature makes it difficult for users to detect until serious damage—such as credential theft, identity fraud, or unauthorized transactions—has already occurred.

Modern spyware families have become increasingly sophisticated. Academic research at Carnegie Mellon (cmu.edu) shows that advanced spyware can avoid detection by security tools through encryption, obfuscation, and process injection. Enterprise-grade spyware used in targeted attacks may also exfiltrate data slowly over encrypted channels to avoid triggering network monitoring systems. Because spyware focuses on data collection, its consequences extend beyond immediate device compromise; it represents a long-term privacy breach that can fuel further cyberattacks.

The most financially devastating form of modern malware is ransomware. Ransomware encrypts files, systems, or entire networks, rendering them inaccessible until a ransom is paid—usually in cryptocurrency. Ransomware attacks target hospitals, municipal governments, manufacturing plants, research institutions, and global enterprises. The FBI (fbi.gov) and CISA label ransomware one of the most severe national security threats due to its potential to disrupt critical infrastructure. Unlike viruses or spyware, ransomware is overt: victims know immediately that they have been compromised, usually through a lock screen or ransom note.

Ransomware has evolved significantly. Early variants relied on simple encryption or social engineering, but modern strains—such as those analyzed by the NSA (nsa.gov)—employ robust cryptographic algorithms, sophisticated propagation techniques, and double-extortion tactics. In double extortion, attackers not only encrypt data but also steal it, threatening to publish sensitive information if the ransom is not paid. Some groups have escalated further to triple extortion, pressuring customers, partners, and employees connected to the victim organization. These tactics highlight ransomware’s shift from technical malware to a full-scale criminal business model.

To understand the differences among these threat categories, it helps to examine their operational goals. Viruses focus on replication and disruption. Spyware focuses on surveillance and data theft. Ransomware focuses on financial gain through extortion. Malware, as the overarching category, encompasses all of these behaviors and more. From a cybersecurity strategy standpoint, recognizing these distinctions informs which defenses must be prioritized. For example, antivirus tools that scan file integrity are effective against viruses, but less so against spyware that hides within legitimate processes. Similarly, ransomware mitigation requires strong backup strategies, network segmentation, and rapid incident response capabilities—protections that are less relevant for basic adware or trojans.

Another key difference involves attack vectors. Viruses often spread through infected files or removable drives. Spyware spreads through deceptive downloads or trojans. Ransomware commonly enters systems through phishing emails, compromised remote desktop protocols, or exploited vulnerabilities. Malware in general can leverage any of these vectors. Understanding the delivery mechanism provides insight into how attackers target users and which preventive measures matter most.

Research institutions such as UC Berkeley (berkeley.edu) emphasize that modern threats rarely appear in isolation. A cyberattack may begin with a trojan, activate spyware to steal credentials, and finally trigger a ransomware payload to encrypt systems. This layered approach increases attack success rates and ensures maximum leverage against victims. Consequently, cybersecurity defenses must also be layered, combining endpoint protection, network monitoring, encryption, user training, vulnerability management, and incident response frameworks aligned with NIST and CISA guidelines.

The distinction between virus, malware, spyware, and ransomware is therefore not merely semantic; it reflects deeper structural differences in how cyber threats function and evolve. Malware represents the broader ecosystem. Viruses replicate. Spyware monitors. Ransomware extorts. Each plays a specific role in the threat landscape, and attackers combine them strategically to achieve their objectives. Recognizing these roles helps individuals and organizations allocate resources more effectively and implement targeted defense strategies.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are viruses still common today?

Yes, although worms, trojans, and ransomware have become more dominant, viruses still circulate—especially in legacy systems lacking modern security controls.

Is spyware used only by criminals?

No. Some commercial spyware tools are marketed for monitoring employees or children, though these raise serious ethical and legal concerns.

Can antivirus software stop ransomware?

It can detect some variants, but ransomware defense requires backups, MFA, patch management, and network segmentation.

Is all malware immediately harmful?

Not always. Some malware quietly collects data for weeks or months before launching its final stage, making detection difficult.

Conclusion

The digital threat landscape continues to evolve, but the distinctions between viruses, malware, spyware, and ransomware remain foundational to understanding modern cybersecurity. Malware is the broad category, viruses replicate, spyware monitors, and ransomware encrypts for extortion. As attackers integrate these techniques into multi-layered campaigns, users and institutions must strengthen defenses through updated systems, continuous monitoring, education, and the adoption of frameworks recommended by leading cybersecurity authorities. In an interconnected world, clarity about these threat types is more than technical terminology—it is a critical element of digital resilience.