Inside the Global Chip Bottleneck No One Is Talking About in 2026

The global chip shortage never truly ended—it evolved. While headlines moved on from the pandemic-era semiconductor crisis, a deeper and more complex bottleneck has quietly taken shape in 2026. Unlike earlier shortages driven by factory shutdowns and logistics failures, today’s chip bottleneck is structural, technological, and deeply tied to artificial intelligence, advanced manufacturing limits, and geopolitical friction.

This new constraint is not about producing “enough chips.” It is about producing the right chips, at the right nodes, with the right tools, and at a scale that current infrastructure simply cannot support. And most of the industry is still underestimating its long-term impact.

The Illusion of Recovery in the Semiconductor Industry

On the surface, the semiconductor supply chain appears stable again. Consumer electronics are readily available, automotive production has largely normalized, and quarterly earnings from major chipmakers suggest recovery. But this stability masks a growing imbalance.

The real pressure point has shifted upstream—toward advanced logic chips, AI accelerators, and leading-edge manufacturing capacity. Demand is no longer evenly distributed across the semiconductor ecosystem. Instead, it is sharply concentrated at the most advanced process nodes, where supply is inherently limited.

This concentration is where the new global chip bottleneck begins.

Why This Bottleneck Is Different From Previous Chip Shortages

The chip shortages of the early 2020s were driven by demand shocks and logistical breakdowns. In contrast, the 2026 bottleneck is driven by technological ceilings.

Key differences include:

- Demand is structurally permanent, not cyclical

- Bottlenecks are tied to manufacturing tools, not factories

- AI workloads dominate silicon allocation

- Capital investment no longer guarantees rapid capacity expansion

In other words, money alone cannot solve this problem.

Advanced Nodes: Where the Real Shortage Lives

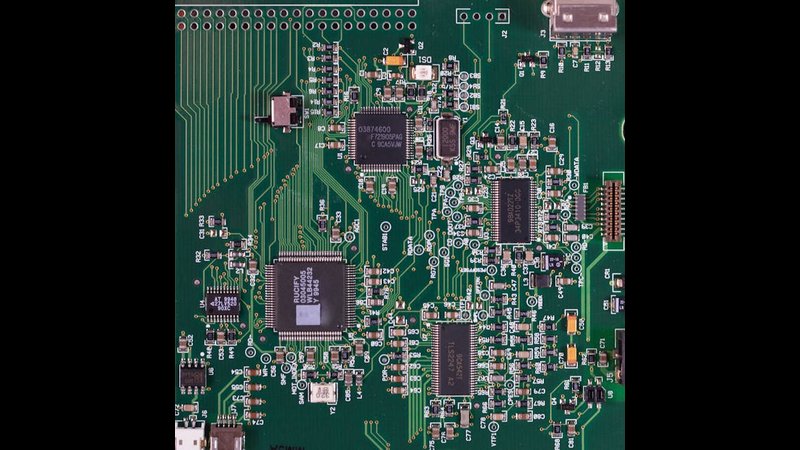

Not all chips are equal. The vast majority of current constraints are concentrated at advanced nodes—particularly those used for AI processors, high-performance CPUs, and data center GPUs.

Only a handful of fabs worldwide can reliably manufacture chips at the most advanced geometries. Even fewer can do so at scale, with high yields.

This creates a choke point where:

- AI accelerators compete with CPUs and GPUs

- Data centers outbid consumer markets

- Supply allocation becomes strategic, not commercial

The result is a silent prioritization of customers and workloads.

EUV Lithography: The Hidden Gatekeeper

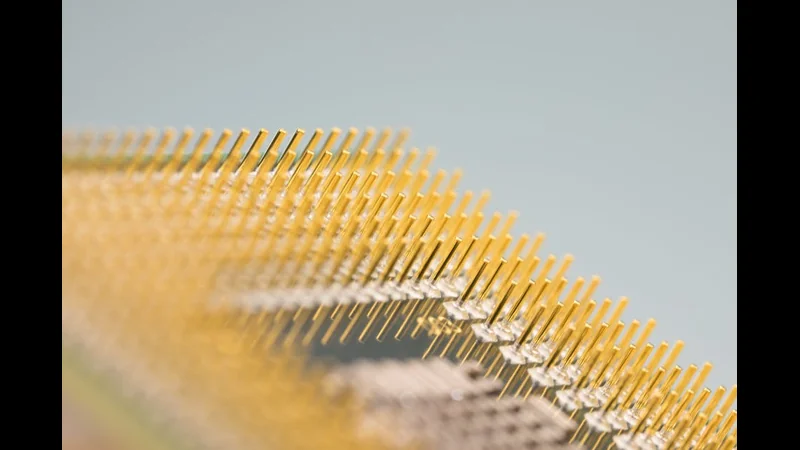

Extreme Ultraviolet (EUV) lithography has become the single most critical dependency in modern chip manufacturing. Without EUV, advanced nodes are impossible.

The problem is not demand—it is throughput.

EUV systems are:

- Exceptionally complex

- Extremely expensive

- Slow to manufacture

- Limited in global supply

Even if a foundry has the capital to expand, it cannot do so without access to these machines. This makes EUV capacity—not silicon—the true bottleneck of 2026.

AI Has Reshaped the Entire Supply Chain

Artificial intelligence is no longer just another market segment. It is consuming an outsized share of advanced silicon production.

AI accelerators:

- Use massive die sizes

- Require leading-edge nodes

- Demand advanced packaging

- Consume disproportionate fab capacity

- As AI workloads scale across cloud providers

- enterprises

- governments

- they absorb capacity that would otherwise serve consumer CPUs

- GPUs

- networking hardware.

This is why consumers may not “feel” the shortage—yet performance gains are slowing, prices are rising, and product availability is narrowing.

Advanced Packaging: The Second Bottleneck

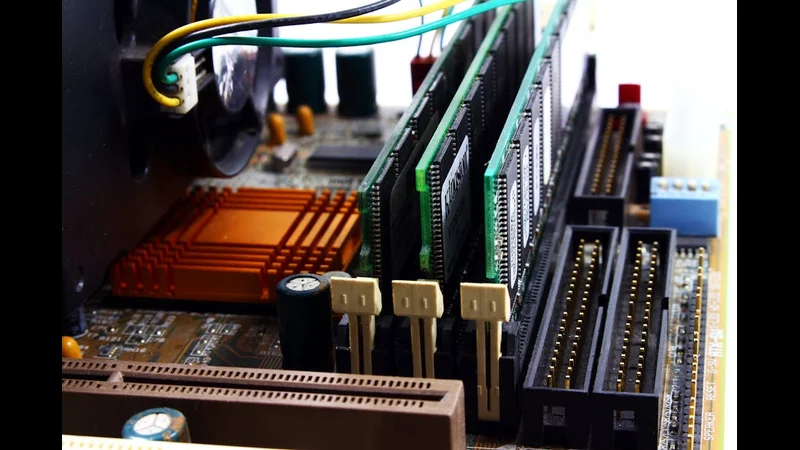

Even when chips are successfully fabricated, many cannot be delivered without advanced packaging technologies.

Modern high-performance chips rely on:

- Chiplets

2.5D interposers

3D stacking

High-bandwidth memory integration

Packaging capacity has not scaled at the same pace as fabrication. This creates a second bottleneck where finished silicon waits for assembly—delaying deployment across entire industries.

Geopolitics and Supply Chain Fragmentation

The semiconductor industry is no longer globally optimized—it is politically constrained.

Export controls, technology restrictions, and regionalization efforts have fragmented what was once a highly efficient global supply chain. While these policies aim to improve resilience, they also reduce flexibility and increase friction.

The unintended consequence is slower scaling, duplicated investment, and reduced overall efficiency—amplifying existing bottlenecks rather than relieving them.

Why Consumers Aren’t Talking About It—Yet

This bottleneck remains largely invisible to end users for now. Devices still ship. Products still launch. But the signs are there:

Slower generational performance gains

Higher prices for high-end hardware

Limited availability of top-tier components

Increased reliance on software optimization over hardware improvement

What appears to be innovation slowdown is often capacity constraint in disguise.

The Long-Term Impact on Innovation

When access to advanced silicon becomes limited, innovation priorities shift.

Companies begin to:

- Optimize software instead of advancing hardware

- Extend product lifecycles

- Reduce risk-taking in chip design

- Focus on incremental gains

- This has long-term consequences for the pace of technological progress

- particularly in areas like AI

- high-performance computing

- advanced graphics.

Can the Bottleneck Be Solved?

In the short term, no.

In the long term, partial relief may come from:

- New fabs reaching maturity

- Improved yields at advanced nodes

- Alternative architectures

- Greater efficiency per transistor

However, none of these solutions scale quickly. The semiconductor industry operates on timelines measured in years, not quarters.

What This Means for 2026 and Beyond

The global chip bottleneck of 2026 is not a crisis—it is a constraint. A persistent, structural limitation that will shape technology development for the rest of the decade.

Those who understand it early—developers, companies, and policymakers—will adapt. Those who ignore it will continue to ask the wrong question: “Why aren’t chips cheaper and faster?”

The real question is whether the world can build advanced silicon fast enough to keep up with its ambitions.

FAQ

Is there still a global chip shortage in 2026?

Yes—but it is concentrated in advanced chips, not consumer-grade silicon.

Why does AI make the problem worse?

AI chips consume disproportionate manufacturing and packaging capacity.

Will prices keep rising?

For high-end and advanced hardware, upward pressure remains.

Can new fabs fix this quickly?

No—fab construction and ramp-up take many years.

Is this a permanent problem?

It is long-term, but not permanent. Progress will be slower and more selective.

Conclusion

The most important global chip bottleneck of 2026 is not making headlines because it is not dramatic—it is systemic. It lives in lithography tools, advanced packaging, AI demand, and geopolitical friction. It does not stop production; it quietly reshapes priorities.

And by the time it becomes obvious to everyone, its effects will already be locked into the next generation of technology.